Name

Charles Wilsher

Conflict

First World War

Date of Death / Age

24/03/1918

Rank, Service Number & Service Details

Lance Serjeant

G/15042

Duke of Cambridge’s Own (Middlesex Regiment)

21st Bn.

Awards: Service Medals/Honour Awards

British War and Victory medals

Cemetery/Memorial: Name/Reference/Country

ARRAS MEMORIAL

Bay 7.

France

Headstone Inscription

NA

UK & Other Memorials

Pirton Village War Memorial, St Mary’s Shrine, Pirton, Methodist Chapel Plaque, Pirton

Biography

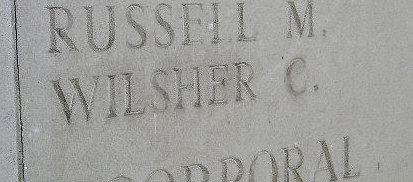

Recorded as Wilsher by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission, on the Soldiers Died in the Great War database and on his memorial in Arras, but as Wilshere on the Village Memorial. His great niece confirms that Wilsher is the correct spelling for this man.

Parish and census records confirm seven children(*1) for James Wilsher and Sarah (née Larman), but by 1911 one had died. Charles eas born in Pirton was baptised in 1878 and, presumably, born the same year.

It was not without good reason that the local papers used the headlines ‘Pirton’s Patriotism’ and ‘Pirton’s Sacrifice’, as many Pirton families had more that one son serving his country. The Wilsher’s were another such family and Charles, Frederick, Arthur and Bertram, all served. Apart from Charles, all survived, but Frederick was badly wounded and sadly lost a leg.

In 1891 Charles was working as a farm labourer. He is absent from the next Pirton census, but he can be found at 169 Cornelia Street, in the London census of Islington for 1901. He was boarding with the Walker family, also from Pirton, and was working as a general labourer. Confusingly, he seems to be absent from the 1911 census. There is a Charles Wilsher living in Islington of the right age, but he is recorded as being born in Islington. No corresponding record for this man, born in Islington, was found in the 1901 census and no record for the man, born in Pirton, was found in the 1911 census, so it could be an error and he could be our man. However, this information should be treated with caution because the later census records Charles as having been married for eleven, or possibly twelve years – the census entry has been amended, and consequently that fact should have appeared in 1901, but did not. If this is our man, then he was living at 32 Canonbury Avenue, Islington, his wife’s name was Evelyn and they had six children, Irene, William, Albert, Basil, George and Elesie(sic) all aged between eight and one. This man was working as a milk carrier at a nearby dairy hall.

Charles was not one of the first to enlist, but was not far behind. The Parish Magazine recorded his enlistment in the 21st Battalion, Middlesex Regiment in 1915 and before August. This would have been his local Regiment and a service battalion formed for the duration of the war. It was actually formed on May 18th 1915 at the request of the Mayor and his Borough. They were stationed in Aldershot and Witley for training and went to France in June 1916.

At this time his parents were living in Andrew’s Cottages - the three cottages at the bottom of the High Street. By April 1917 they heard that another son, Frederick had lost a leg. Then came more worrying news; Charles wrote from the First Australian General Hospital in France, to let them know he had been wounded (on Easter Monday) ‘We were advancing, when the Germans let the machine guns go, and I got a bullet. It went in at the top of the buttock and stopped just above the back of the knee.’ They took the bullet out on the 14th he added bravely and reassuringly ‘I feel much better now. Nothing to worry about.’

He returned to Pirton for recuperation and, although it should have been a happy prospect, he must have had mixed feelings when he found that his visit coincided with two of his brothers also being in Pirton – Frederick, waiting for his formal discharge following the loss of his leg, and Arthur, who had also been wounded.

Charles recovered and returned to service and we have no more news of him until a newspaper report of May 2nd 1918, under the heading ‘Three Men Missing’ Charles Wilsher’s name is one of them. This information was repeated two days later, on June 6th and then again in the August Parish Magazine. Without any firm news the family must have hoped for the best and feared the worst.

We know that Charles died on March 24th 1918 and that date was during the period of the German Spring Offensive, which may explain some of the delay in getting news back to Pirton, but why the family could not be informed sooner is not known. Sometimes news of the deaths of non-commissioned officers and the lower ranks, given its importance to their families, travelled at an uncomfortably slow pace, especially when compared to the telegram which normally informed of an officer’s death. The Battalion’s war diary helps piece together the last three or four days of his life.

On March 21st the Germans launched a huge offensive, with sixty-five Divisions attacking along a 60 mile front. They knew that massive numbers of American troops would be entering the war and they needed to strike a decisive blow before they could change the outcome. General Erich Luderndorff masterminded and ordered the offensive. ‘We must strike at the earliest moment before the Americans can throw strong forces into the scale. We must beat the British.’ He had reinforced his army with 500,000 battle-hardened troops from the Russian front. The British were targeted with the aim of splitting the French and British troops. They concentrated crack troops on the weaker sections of the lines and almost ignored the stronger sections, effectively leaving them isolated to be strangled at will when the line along the Western Front had been broken.

Initially they were hugely successful, the British were forced further and further back to shorten the defensive line and to avoid being outflanked. The retreat varied from a structured withdrawal to near rout, but they fought all the way. By the end of the first day the British had nearly 20,000 dead and 35,000 wounded.

By the 24th, the date given as Charles Wilsher’s death, the Germans were jubilant and claiming almost complete success, but they had moved forward at such speed and with such success that their troops were exhausted, they were running out of supplies of all kinds and the attack began to peter out between the end of March and early April.

In those few days the Allies lost 255,000 men and the Germans 239,000. It was near chaos and so it is not surprising that facts surrounding Charles Wilsher’s death are confused.

The war diary of his Battalion provides more specific information on what Charles experienced, although still describing a very confused situation. At the start of the offensive (March 21st) they were at Boisleux-au-Mont South of Arras. Charles and his Battalion were ordered to move to Henin Hill before the Germans could occupy it. They moved in the early evening, taking up position by 3:00am, but later that day they were ordered to Sensée Valley, north-east of Ervillers, where they were to be the reserve for the 121st Brigade, who were holding a position near St. Leger. At 2:00pm they were ordered to reinforce the Welsh Regiment at Croisilles Switch and by 6:00pm they recorded that the troops in front of them were being driven back and, very soon afterwards, the Middlesex were fighting the German advance troops. It seems that they held position or at least were not forced back too far because on the 23rd the war diary records that they counterattacked.

The situation was chaotic and the fighting and shelling was fierce; between the 21st and then 25th the Middlesex diary records their losses as 2 officers and 21 other ranks killed, 6 officers and 189 other ranks wounded, 6 other ranks wounded and missing, and 2 officers and 80 other ranks missing. Charles Wilsher’s body was amongst the missing.

He, like 34,749 other men with no known grave, and who died in the Arras sector between the spring of 1916 and August 7th 1918, is commemorated on the Arras Memorial. This memorial is hugely impressive and stands fortress-like on the western outskirts of the town. Its high walls protect the honoured names, the 2,651 Commonwealth burials and the peace within. It has ten bays to record the names. Charles Wilsher’s name is in Bay 7, not that far from five other men listed who appear on Pirton’s memorials or who at least have some Pirton connection.

(*1) Martha (b c1876), Charles (bapt 1878), Frederick (b 1882), Kate (b 1884), Robert (bapt 1885), Arthur (b 1887) and Bertram (b 1890).

Additional Information

Text from the book: The Pride of Pirton

Acknowledgments

The Pride of Pirton book – Chris Ryan / Tony French / Jonty Wild