Name

Frank Abbiss

Conflict

First World War

Date of Death / Age

25/12/1918

Rank, Service Number & Service Details

Private

201339

Norfolk Regiment

1/4th Bn.

Awards: Service Medals/Honour Awards

Not Yet Researched

Cemetery/Memorial: Name/Reference/Country

ALEXANDRIA (HADRA) WAR MEMORIAL CEMETERY

H. 65.

Egypt

Headstone Inscription

Not Researched

UK & Other Memorials

Pirton Village War Memorial,

St Mary’s Shrine, Pirton,

Methodist Chapel Plaque, Pirton,

Pirton School Memorial

Biography

Frank was born on November 13th 1880 to George and Ann Abbiss. The 1911 census records that they had seven children(*1), but that three had died. Two remain unnamed to us. The two brothers that survived were Frank and Harry, who served and Harry survived. Although born ten years apart both Frank and Harry went to the Pirton School and, when they left, both went on to work on local farms.

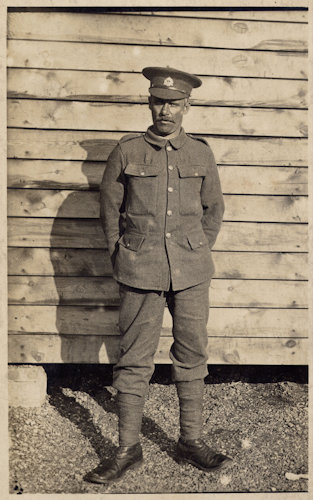

The 1911 census shows that Frank was still living in Pirton, but when and where he enlisted is not known, as his enlistment is not recorded in the Parish Magazine, although another man of the same name is, and his service record is one of those destroyed in the Second World War. It is interesting to note that the Pirton memorial records his regiment as the 1st Bedfordshires, but we know he was serving with the 1/4th Battalion, Norfolk Regiment when he died. A poor quality photograph was found in 2012 and was identified by others as Frank Abbiss. A better photograph was found appearing to be of the same man. Careful analysis of both photographs reveals his cap badge to be a Bedfordshire Regiment’s, so we have another conundrum. Both photographs were probably taken during training, so it seems most likely that Frank enlisted in the Bedfordshires and was later transferred to the Norfolks, possibly following wounding or illness or simply to bring them back to strength. Perhaps another possibility may relate to the fact that the 5th Bedfordshires were in Egypt at the same time as the 1/4th Norfolks, even swopping positions. His medal rolls index card list two service numbers the one above and an earlier one 5703, perhaps another clue.

Obviously Frank’s experience of the war would have been much the same as his Battalion’s for the duration of his service, but without any more information we cannot know when that began. For that reason the experience of the 1/4th Battalion from its first campaign is given as Frank’s. The campaign he is least likely to have served in would be the Gallipoli Campaign in 1915, but if he enlisted in 1914 his training would have finished around the time that the Battalion left for the Dardanelles, so it is possible that he was with them.

On July 29th 1915 the 1/4th Battalion boarded the H.M.T.(*2) Aquitania. The next day they set sail to join the 163rd Infantry Brigade in the 54th Division as part of the Mediterranean Expeditionary Force and to reinforce the Gallipoli Campaign which had started in February. On August 9th they disembarked at the Isle of Lemnos, just off the western coast of Turkey, and transferred to the S.S. Osmanieh to continue. They landed at Suvla Bay, Gallipoli, on the 10th. They were very lucky, as they appear to have landed without interference; in other landings thousands were slaughtered on the beaches. The next day they entered the reserve trenches and then went into action against the Turks. Shelling of the base camp began on the 14th and in the following days “A” and “B” companies and “C” and “D” companies took turns between the reserve and the front line trenches. The war diary provides no detail of their action, but between the September 2nd and 30th they suffered 81 casualties. In October there were 24 casualties and only 6 in November. Then between December 7th and 8th they embarked for Mudros – a port on the small Greek Island of Lemnos and on the 16th, on board the H.M.T. Victorian, they headed to Alexandria, Egypt, leaving the Gallipoli campaign behind them.

The Gallipoli Campaign was a disaster. Originally it was the idea of Winston Churchill, then the First Sea Lord of the Admiralty. The intention was to open another front and ultimately pull some of the Germans forces away from Europe. The British, Australian and New Zealand forces landed with thousands killed in the process. They fought hard to get off the beaches, but the war quickly reached a stalemate. Supplying the army was extremely difficult; water was scarce and dysentery rife. There were over 200,000 allied casualties from the fighting and dysentery. The one real ‘success’ was the amazing evacuation of 105,000 men and 300 guns from Anzac Cove and Suvla Bay. The withdrawal officially began after Frank’s Battalion had left and it took place over several weeks. During the last phase elaborate ruses were used to make the Turks believe the Allied forces were still in the trenches and they withdrew without a man being killed. Apparently the Turks were still firing on the empty trenches some hours after the withdrawal was complete.

In Egypt, where the Norfolks went, the enemy was the Ottoman Empire (the Turks) who were helped and advised by the Germans. The Norfolks spent the whole of January 1916 in the Sidi Bishr area of Alexandria (sometimes written as Bishi), receiving training and then moving to Mena Camp, which was near Cairo and within sight of the Pyramids. This would have been an exotic experience for a villager from Pirton, although during February and March they were kept busy training and integrating replacement men into their ranks. At the end of March they moved to Shallufa just a few miles north of the Suez Canal. War was getting closer again and the enemy was reported as attacking another part of the line on April 24th. They stood to arms and were asked to maintain great vigilance, but nothing occurred. They continued their general defence work until May 28th when they entrained for Serapeum, some 38 miles south, at the other end of the Bitter lakes and near the Suez Canal. Here they were positioned to defend the Canal.

During June the enemy dropped five bombs, but there were no casualties and there was no fighting, but the war diary records 2 casualties; 1 man died ‘wounds self-inflicted’ and 1 drowned while on duty. The Battalion continued with its duty of ‘Guards, Outposts, Patrols, Fatigues and Training.’

In late July they moved 20 miles north by train to El Ferdan. Then in August they moved back to Serapeum, where they stayed until January 1917, then moving first to Serapeum West and then Moascar. The war diary notes no significant events just more ‘Guards, Outposts, Patrols, Fatigues and Training.’ The most exciting experience, at least for some of the men, was a trip to the seaside camp at Sidi Bishr during September and October. On the whole it sounds boring and monotonous and probably was, just one long round of routine, undertaken in the sun and heat.

In February they were once again on the move, but this time on foot. Between the 1st and the 28th they marched from Moascar (Al Isma'iliyah, Egypt) to El ‘Arish and then to Khan Yunis (Khan Yunus) just 160 miles or so in 28 days and in scorching heat. They remained in that area before marching another 25 miles in late March to In Seirat (south of Gaza and in Palestine). They were about to enter the First Battle of Gaza, which commenced on March 26th. It was a two-day battle and the British almost won. In fact they came so close that the German commander, Major Tiller, destroyed his wireless set and prepared to surrender. Unfortunately, through lack of efficient communications, the British did not know this. Turkish reinforcements were spotted and it was thought that there was a danger of the British troops being cut off. The troops were ordered to new positions causing confusion. The Norfolks entered the trenches on the 27th with orders to prepare to repel an attack. They were shelled and 2 men were killed and 13 wounded. Eventually the British had to pull back and consolidate. The British suffered over 4,000 casualties during the battle; 523 dead, 2,932 wounded and 512 missing. It is estimated that the Turkish casualties were only 2,450.

A second battle was planned to start on April 17th. By this time the Norfolks were at Sharta. They moved into a position to provide support to the 1/8th Hants and the 1/3rd Suffolks. On the 19th the Norfolks moved forward into the attack. That is all that the war diary records; it adds no detail about the battle other than the Battalion casualties; 42 killed, 12 died of wounds, 317 wounded, 2 wounded and missing, 92 missing, 6 taken prisoner of war and 6 slightly wounded. Of around 1,000 men, 17 officers and 460 other ranks were recorded as casualties; it must have been horrendous. At 6:00am the next day they withdrew. The losses were so great that they had to join with the 1/8th Hants to form a composite battalion.

A report on the action was added later. The attack commenced at 7:30am and the Battalion went forward in two lines over a ridge. The first line was immediately met with shrapnel shells and machine gun fire. They spread out to reduce casualties, as did the second line and got about 100 yards before being forced down. They rose up and moved forward, covering about 500 yards and getting to within 150 yards of the Turkish redoubt, but they had lost a lot of men. The 1/8th Hants came up to reinforce the attack and, with the help of the 1/5th Norfolks, reached the redoubt at about 9:00am. By then ‘the Battalion were not strong enough to attack the trenches’ but they held position awaiting reinforcements. ‘No reinforcements arrived and after about three hours owing to ammunition being nearly expended superiority of fire could no longer be maintained’ - they suffered more heavy casualties during this stage. Believing that an order to withdraw had been issued they began to retire, but realised that the line was still being held to their right. This could have left those soldiers desperately exposed, so with amazing discipline and incredible bravery they checked the withdrawal and tried to re-establish the line. The Commanding Officer became a casualty. The only unwounded officer 2nd Lt J H Jewson took command and, waiting until dusk, completed the withdrawal trying to bring the wounded with them. Seven medals were won but hundreds of men were lost.

The British attack was defeated and in this, the Second Battle of Gaza, the British received another 6,444 casualties. Turkish casualties were estimated as only 2,000. The Army withdrew, dug in and consolidated again. It was a heavy defeat and they remained in defensive positions, undertaking working parties or training and awaiting new men to bring them back up to strength. The Norfolks were out of action and behind the lines until early September. Even so they were not completely out of danger and occasionally their bivouacs were shelled. They returned to the front line trenches but without much in the way of incident. By the end of the month they were back to within 200 or so of full strength.

They saw some action in November between the 1st and 7th when, following an artillery barrage, they attacked the Turkish lines; there were a few casualties, but nothing compared to the early scale. They experienced some success and the Turks responded with gas while the Norfolks tried to consolidate. During November their casualty list was 21 men killed, 4 died of wounds, 106 were wounded but remained at their posts, 5 were missing, including 1 believed wounded, and 1 believed killed – another 136 men and, very unusually all, including the ‘other ranks’, are named in the diary. Frank was lucky not to be among them.

Despite the major set backs earlier, from October 1917 the British were beginning to win the war in the Middle-East. The tide was turning and on December 11th 1917 Jerusalem fell – a major success for the British.

In December the 1/4th Norfolks moved from Haditheh to Deir Turief and to Yehu Diyeh (believed to be Tell eh-Yehu-diyeh, Egypt) and relieved the 5th Bedfords and the 1/10th Londons. Another quiet time, but in an attack by the Turks on the 11th and the preceding shelling, there were another 55 casualties. On the 15th the Norfolks returned the compliment but suffered another 80 casualties. The official report adds that ‘out of a total of 6 officers and 219 other ranks who carried out the attack, nearly all these casualties being from M.G, fire during the advance.’ Again at the end of the month the casualties were summarised including the above, and again all were named; 30 men killed, 89 wounded, 22 others were wounded and had since died – 141 men.

They had fought long and hard, suffered high numbers of casualties and deserved some respite. The war diary for the next few months indicates that is what they got and, although there were occasional enemy actions, it was mostly training, fatigues, patrols and the inevitable working parties. Effectively they were out of the ‘real’ action until the middle of June 1918 and at the end of the month they moved to Surafend in Palestine.

August and September 1918 were mostly quiet with more training and the standard working parties and patrols, but they did move on several occasions to new camps and positions. On September 19th and 20th one and a half companies were detailed to attack the Turks at Sirisia, but the Turks withdrew before the attack. The Norfolks pursued them to the village of Bidieh. They paused and then the next day moved forward only to find that the Turks had withdrawn again, this time in even more haste, leaving an enormous amount of artillery ammunition, a gun and several wagons behind. Casualties were nil. The Norfolks moved from Bidieh to JilJulish for a few days’ cleaning and training before moving to Kakon, then Kakkur, Zimmarin and then at the beginning of October to Athlitt and the port of Haifa - about sixty miles through Palestine and the area that is now Israel. There then followed more training, fatigues and working parties plus guard duties. But in late October they moved yet again to Acre on the 24th, then in the following days to, Musheirefeh, Ras El Ain, Nahr El Kasimyreh, Ain Barak, Saida and finally to Ed Damur.

Although the war diary provides no explanation, something was amiss with the Battalion numbers; at the end of September its strength was given as 33 Officers and 863 other ranks and then at the end of October, although difficult to read, it appears to be 27 Officers and 693 other ranks. Only 1 officer and 29 other ranks were recorded as casualties of the recent march, some of whom had gone to hospital. In November they moved again ending up in Beirut; interestingly there is no mention of the armistice in Europe on the 11th. From here the Battalion, now consisting of only 19 officers and 441 other ranks, boarded two ships, the H.T. Ellenga and the H.T. Hunslet, and left Beirut bound for Kantara in Egypt. Two days later, on November 30th 1918, the Turkish army surrendered to the British. Amazingly this event is also given no comment in the diary.

From the numbers given above the Battalion strength seems to have dropped from 896 to 460 without much in the way of comment. Perhaps some men had gone ahead to Kantara, which might explain a substantial proportion, but the numbers still do not seem right. From Kantara they moved to a camp at Halmieh and on December 7th, 8 Officers and 247 reinforcements ‘rejoined’ from Kantara. The grammar used does not make it clear whether all or just some of these men were rejoining from hospital, but on the 9th 5 Officers and 41 other ranks rejoined, on the 10th 41 more other ranks and on the 11th, 32 more other ranks rejoined and all were rejoining from hospital. Although no detail of why the men were hospitalised appears, it is clear that there must have been major illness within the Battalion. The illness could have been any of a number of diseases that were rife such as dysentery, but it could also be the Spanish influenza pandemic, which had been gathering pace during 1918. Lyn MacDonald’s excellent book, The Roses of No Man's Land(*3), confirms that there were many cases in the hospitals at Alexandria around that time. She quotes the fact that VAD Nurse Kit Dodsworth of No. 19 General Hospital in Alexandria, Egypt, heard about the Armistice being signed ‘after a busy day caring for victims of an influenza outbreak that cost many lives.’

Originally it seemed likely that it was Spanish influenza that killed Frank, however, incredibly, original information papers turned up including one from the Cemetery Record Office which was found in the summer of 2010 in the Rectory Manor House. It was presumably there because one of his sisters married into the Weeden family who owned the house. One, dated November 26th 1918, was sent his parents and warned that he was dangerously ill at 19 General Hospital Alexandria. Another clarifies the cause of death as dysentery.

He had survived past the end of the war in Europe and in the Middle-East. He had survived the horrendous numbers of casualties that his Battalion had suffered, only to die on Christmas Day 1918.

He is buried far from Pirton, in the Alexandria (Hadra) War Memorial Cemetery, Egypt - Hadra is a district on the eastern side of Alexandria, Egypt. The cemetery contains 1,700 First World War burials and, as most were from the hospitals, almost all are identified.

(*1) Frank (b 1880), Elizabeth, Mary (known as Polly, b c1882), Charles (b 1884, d 1887), Harry (b 1890), and Frederick (b 1892, d 1893).

(*2) H.M.T. = His Majesty’s Troopship.

((*3)) Published by Michael Joseph ltd, ISBN 0-7181-1785-9.

Additional Information

Text from the book: The Pride of Pirton

Acknowledgments

The Pride of Pirton book – www.pirton.org.uk/prideofpirton Chris Ryan / Tony French / Jonty Wild