Name

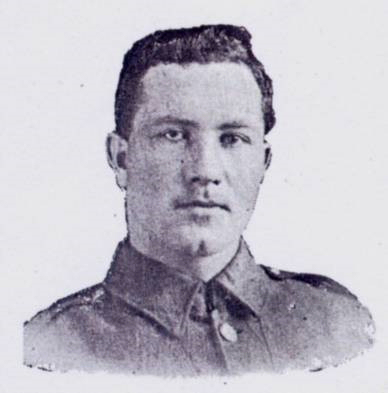

Walter Reynolds

Conflict

First World War

Date of Death / Age

02/12/1917

23

Rank, Service Number & Service Details

Private

242137

Gloucestershire Regiment

2nd/5th Bn.

Awards: Service Medals/Honour Awards

British War and Victory medals

Cemetery/Memorial: Name/Reference/Country

CAMBRAI MEMORIAL, LOUVERVAL

Panel 6.

France

Headstone Inscription

NA

UK & Other Memorials

Pirton Village War Memorial, St Mary’s Shrine, Pirton, Methodist Chapel Plaque, Pirton, Pirton School Memorial, St Mary's Church Roll of Honour (Book), Hitchin, 4 Coy' Hertfordshire Reg' Territorials Memorial, Hitchin

Biography

The family of Lewis and Mary Ann Reynolds (née Catterell) was a large one. Baptism and census records list fifteen children(*1), born in the space of fifteen years, but by 1911 five had died. Walter, born on September 20th 1894, was their youngest, one of six to serve, and the first of two to die. A newspaper commented, ‘Few families can show a better record of war service’.

The family lived in 3 Wesley Cottages - the group of cottages behind the terrace which now contains the village shop and Walter grew up following the common Pirton pattern; Pirton School then labouring locally. By the time war came his mother had been an invalid for several years and he was working for his father on the family’s smallholding. He joined the Hitchin Territorials with other friends from Pirton, and was one of the first to volunteer to serve overseas and so joined the 1st Hertfordshire Regiment.

Although he joined the 1st Battalion, Hertfordshire Regiment as Private 002361, he was attached to the Gloucestershire Regiment and was eventually amalgamated into it as Private 242137. A newspaper article reports that he ‘went to France May 24th 1916’ and elsewhere it is recorded that the 2/5th Battalion of the Gloucestershire Regiment landed in France on May 23rd 1916. With two such similar dates it seems likely that he was already in the Gloucestershire Regiment by that date or was transferred on arrival.

The Gloucesters had battalions in France from the very beginning of the war and in 1915 had battalions at the Second Battle of Ypres, Loos and Gallipoli, but they were all before Walter’s service. By the summer of 1916 they were at the Somme. However they were lucky and were not in action on the first day, when in the confused carnage there were nearly 60,000 casualties in the British Army.

By March 1917 they must have felt that they were winning as they pursued the German Army from Caulaincourt to Vermand, but this was a planned withdrawal to the heavily fortified Hindenburg Line. This advance was described by Captain R.S.B. Sinclair of 2/5th Battalion:

‘. . . patrols were sent forward to ascertain if the village of Vermand had been evacuated. This was found to be the case and “A” Company was sent up to consolidate east of the village. Whilst digging we saw Uhlans(*2) skirmishing in Holnon Wood . . . they made off towards Bihecourt, about a mile east of Vermand and our rifle fire had no effect on them. This was the first and only time that I saw German Cavalry in the War.’

Interestingly, three celebrated war poets came from Walters’s Regiment; Captain Cyril Winterbotham, Lieutenant Will Harvey and Private Ivor Gurney. Will Harvey (DCM) was captured in August 1916 and completed a slim book of his poetry called ‘Gloucestershire Friends: Poems from a German Prison Camp’, which surprisingly his German captors forwarded, untouched, for publication in England in 1917.

In the summer of 1917 they were involved in their next big battle, the three-month long Third Battle of Ypres. The appalling conditions in which the battle was fought have been described earlier, for the other Pirton men who died in it. Here it is enough to say that it was fought in a quagmire of mud.

In between, major attacks, raids and counter-raids were launched. One of the captains of Walter’s Battalion, Captain M.F. Badcock, wrote to his wife describing a typical example; perhaps Walter was part of it:

‘I have done a raid show. It did not go badly: we collared some prisoners, one machine gun, and did in about twenty. . . . . . . The wretched Germans were simply mad with fright and it seemed sheer butchery, all poor youths of eighteen and nineteen. We got ten prisoners, but six were killed going across No Man's Land by their own shells; one fool surrendered to me and thrust at me with his bayonet; it went through my trousers, tore my pants, and never touched me. There was nothing to do but to shoot him. It's the first life I have ever taken in this war to my certain knowledge and it was beastly. We did not have a single fellow killed, only four slightly wounded and all got in safe, so it was a success. Our fellows absolutely saw red and we had a job to stop the killing. We blew up three of their dugouts, which they would not come out of, so I suppose they were buried and suffocated.‘

By the end of this battle, which was November 10th 1917, the British and their Allies had advanced about 4 ½ miles. The British had lost about 310,000 men and the Germans 260,000.

Perhaps surprisingly, Walter did get some respite from this battle. He was home on leave in late October, but upon his return he was heading towards another – The Battle of Cambrai.

This battle commenced in the ‘usual’ manner. At 6:20am key German targets were hit with heavy artillery fire. This was followed by smoke to confuse and blind the enemy and then a creeping barrage – intended to stay just ahead of the attacking force and act as a protective curtain by forcing the enemy to take cover. The difference in this battle, compared with others, was the significant use of tanks. Some 350 attacked supported by the infantry. The attack was initially very successful and some five miles of ground was won and, most importantly, the Hindenburg Line, which the Germans had believed to be impregnable, was breeched. The Germans reorganised, reinforced and then counter attacked on November 30th and, as had happened so many times before, the gains were lost. By December 3rd, General Douglas Haig ordered the troops, who were still near Cambrai, to withdraw to shorten the ragged front line into a more defensible position. By then 179 tanks were out of action and there had been 44,200 casualties on the British side and a similar number for the Germans.

Walter died on the 2nd while on his way to the front line, the day before Haig ordered the withdrawal. He and others were resting near an ammunition dump, which was not a good position to choose, because it exploded, presumably due to a shell hit. The Rev. J Panton, a Wesleyan chaplain wrote to his parents with this information. He added that ‘Death was instantaneous’ – it is hoped that this was true, but this phrase was all too often used so that relatives did not think their boy had suffered.

His Commanding Officer, CF Hamilton also wrote, ‘These men are all so splendid out here and you have every reason to be proud of them, but it is hardest of all for you at home, as the men themselves say. You must try and keep a brave heart as he would wish and a bright hope for the future. God bless and comfort you.’

Although the Rev. J Panton confirmed that Walter’s remains were interred, this may also have been a ‘kindness’. In any case, either his body was not found or the burial site was lost or destroyed after their withdrawal, because after the war Walter’s grave was not recorded and so he is remembered on the Cambrai Memorial. It is smaller than some, but this memorial’s entrance is still imposing and it stands on the side of a country road between Bapaume and Cambrai, near the small village of Louverval. His name appears on Panel 6, situated on the rear boundary, beyond a small number of burials - one of 7,043 names of men with no known grave.

Officially he died on December 2nd, but the family believed that it was the 3rd, and that there was a grave that they could visit.

Apart from Walter five other brothers were also serving; William, Albert, George, Harry and Jacob. All survived except Albert who features later in this book.

Walter and Albert are also remembered on their parents’ grave in St. Mary’s churchyard.

(*1) James (bapt 1870, d 1871 aged seven months), Clara (bapt 1872, d 1874 aged two years), Maria (bapt 1874), Jacob (bapt 1876), Peggy (bapt 1877), Daisy Emma (b 1879, possibly d 1900 aged twenty), Mary (b 1881), William (b 1883), Albert (bapt 1884), Abigail (b 1886), Sarah (b 1888), George Thomas (b 1890), Harry (b 1890 and George’s twin), Emily Agnes (b 1893) and Walter (b 1894).

(*2) The Uhlans were the German light cavalry.

Additional Information

Text from the book: The Pride of Pirton

Acknowledgments

The Pride of Pirton book – www.pirton.org.uk/prideofpirton Chris Ryan / Tony French / Jonty Wild