Name

George Charlick

Circa 1888

Conflict

First World War

Date of Death / Age

17/06/1918

39

Rank, Service Number & Service Details

Private

698133

London Regiment *1

1st/22nd (County of London) Bn. Formerly 452330, 2/11th Bn., *2

Awards: Service Medals/Honour Awards

British War and Victory medals

Cemetery/Memorial: Name/Reference/Country

POZIERES MEMORIAL

Panel 89.

France

Headstone Inscription

NA

UK & Other Memorials

Pirton Village War Memorial,

St Mary’s Shrine, Pirton,

Methodist Chapel Plaque, Pirton

Biography

George shared his name with his father, who was also George Thomas Charlick and his mother’s name was Elizabeth. He was their eldest son, born around 1888, and had two siblings; Ernest Nugent (b 1889) and Louisa M (b c1892) - Ernest was recorded as Edward in the 1901 census.

In order to establish George’s connection to Pirton it was necessary to analyse information for the rest of the family. His parents were from Enfield, Middlesex and Eaton, Bedfordshire respectively. They married in 1887 and the 1891 census shows them to be living with their young boys in 4 Cleveland Terrace, Totteridge Rd, Enfield. George (junior) was born in Ponders End, Middlesex and the other children in Enfield. George (senior) worked as a gunsmith and his younger brother Alfred J shared their house and also worked as a gunsmith. Quite probably both men worked at the Royal Small Arms Factory at Enfield Lock. By 1901 the family had moved to Warley Road, South Weald where George (senior) had become a publican in an ale house, possibly called The Brass Hare, but the census writing is hard to decipher.

It was hoped that the early release of the 1911 census data would help with George’s details, but there are no George Charlicks (or similar names) with sufficient corresponding information to attribute their details to George (junior) with any confidence. His sister is missing, but she had probably married and changed her surname. Ernest had become a policeman and was boarding with the Cartwright family at 265 Monega Road, Forest Gate and their parents had moved to Eynesbury, St. Neots, Huntingdonshire (now Cambridgeshire). George (senior) was ‘working on own account’ as a beer retailer in The Hare and Hounds – presumably the same pub that still exists today in Berkley Street. It is possible that they had first moved to The Jolly Plough Boys beer house in Chawston, Bedfordshire, in 1904, as the landlord is recorded as George Charlich – a possible transcription error. There are no Charlicks listed in Pirton in 1911 so it seems that the family connection with Pirton began some time between 1911 and October 1914, when George seniors name appears in the Hertfordshire Express newspaper report featured in the biography for Henry Chamberlain ‘WAR AGAINST SPECIAL CONSTABLES’ - the full report is included in the reference section of this book. Although George (senior) was fifty-one and could not have been in Pirton for very long, he had become a special constable and would therefore have been a well known and respected member of the community. His part in the ‘Exciting Night Scenes at Pirton’ is mentioned elsewhere. In later years, long after the war, George’s brother Ernest came to Pirton to live and George and Ernest’s parents, as well as Ernest and his wife, Minnie Flora Agnes, are buried in St. Mary’s churchyard.

This, of course, only offers information about George's family, not him. His name does not appear in the lists of local men joining up, which suggests that he never lived in Pirton, at least not for any length of time. His parents did however, and in 1918, just one or two months before his son’s death, Mr G Charlick donated two shillings to the carved oak War Memorial Shrine being constructed and which still sits inside Pirton Church.

When George enlisted he was living in Rosebery Avenue, Holborn, and this is where he joined up. He was initially Private 452330, 2/11th Battalion, County of London Regiment (Finsbury Rifles). He was later transferred to the 1/22nd Battalion, County of London Regiment (The Queen's), becoming Private 698133. We know little of George Thomas Charlick‘s personal life, so perhaps it is fitting that his service experience is given more prominence as so much of what he experienced would have been similar for many of the Pirton men who served.

Although it is not certain when he enlisted, in 1915 George would have been about twenty-seven, so it is reasonable to assume that he enlisted early in the war. With this assumption, and the details provided by the war diaries of the two battalions, it seems almost certain that George transferred to the 1/22nd on January 30th 1918 and that what follows was his experience of the war.

The war diary of the 2/11th Battalion confirms that they were part of the 58th Division, 175th Infantry Brigade. In September 1915 they were in training at Woodbridge and Melton and their experience of war was limited to watching Zeppelins flying over Woodbridge and home defence work. The war diary has a gap from February 1916 to January 1917, but other sources indicate that in May 1916 they moved to Bromeswell Heath and then to Longbridge Deverell.

On January 19th 1917 the Battalion finally received its long-awaited entraining orders and a railway timetable. They were ordered to Warminster, Southampton and to Le Havre, France. They arrived in two parties on February 5th and 6th. Within a week they had entered the trenches, where they immediately experienced ‘moderate enemy activity’, watched aerial warfare and saw the British bombardment of the enemy trenches. But on the 16th it was their turn; they had their first experience of an enemy bombardment and they were shelled with heavy, medium and light artillery. Some of the shells contained gas. This was repeated the next day and ‘3 men were badly gassed before their respirators could be adjusted. These 3 died later and another 8 other ranks from the same party were admitted to hospital.’ - their first casualties. They were relieved on the 17th.

Having moved to Halloy, on February 25th and been billeted, they were told that the enemy had retired along the whole front and orders were given: ‘All troops to be ready to move at short notice after 5:00am tomorrow.’ The Germans had begun a planned withdrawal of 25 miles to their prepared ‘impregnable’ defensive positions along the Hindenburg Line. They burnt or destroyed everything as they retreated, leaving a waste land, where, if items of interest or battleground souvenirs were found, they were often booby trapped.

George’s Battalion did not move until the 27th, when over two days they marched to Gaudiempre and then to Riviere, some 16 miles and presumably the location of the new front line. They were back in the lines on March 1st and the diary for the first half of March records a lot of artillery action by the Germans, a good proportion of which included gas shells. The weather cannot have been good as the rain seriously damaged the trenches and some were becoming impassable. In fact they became so bad that they had to withdraw to the support line, but at least the enemy’s activity eased off for a few days in the middle of the month. The relief was temporary as their activity returned with increased ferocity and included machine gun sniping and trench mortars. Explosions were also heard in the German trenches and it was suspected that they were about to withdraw further. They were right and it turned out to be another phase of their planned withdrawal.

From March 18th to May 3rd the 2/11th Battalion were out of the line, and frequently assigned to working parties of up to 300 men. Often the work related to the repair and maintenance of roads and railways. This was vital because of the pressing need to extend the British supply lines to the new front line. Also during this period they had moved from Buire au Bois to Miraumont and then to Achiet le Petit.

On May 4th they moved another eleven miles forward and returned to the trenches. The normal terrors of war were restored over the next two days and the diary records ‘a great artillery activity by both sides . . . . . . trench mortars . . . . . .’ but ‘comparatively quite little shrapnel.’ After eight days, with only 7 men wounded and 1 killed, they marched out of the trenches for six days’ training and rest. By the 20th they were in the right sector of Bullecourt. Having just arrived, their war diary, with unusual frankness, gives an insight into the conditions ‘Trenches were in a very bad state many decomposed bodies lying about and trenches were practically shell holes joined together. Enemy artillery shelled our front support lines intensively from 3:45 – 4:30am with shrapnel and gas causing several casualties. Total for 24 hours 3 killed and 19 wounded other ranks.’

When trench warfare falls into a pattern of apparent monotony, it is difficult to do justice to the men’s experience. From May to July 1917 they were in the trenches for a few days, then rested, formed working parties, carried supplies to the Front or trained and then returned to the fighting. When in the trenches they were in constant danger; just about every day the diary records artillery activity, sometimes light, sometimes heavy, sometimes during the day, sometimes at night, sometimes both. The truth of their experience is indicated by the almost daily punctuation of entries, with casualty figures; ‘several casualties . . . . . 6 other ranks killed, 9 other ranks wounded . . . . . . 3 other ranks killed 4 wounded . . . . . . 2 killed 3 wounded’. ‘Keep your head down’ would have been the sound advice given by the old hands, but you might well be selected for a trench raid such as the one on June 13th: ‘Raiding party consisted of 3 offs (officers) 60 other ranks & was successful killing 20 Germans & capturing 1 off & 2 other ranks’ – usually dangerous, but on that occasion ‘Our casualties 1 other rank wounded.’ After their efforts they were given much of August to train and to recover, and the danger of this area of France disappeared as they marched to Arras station, to board a train to Belgium and the Third Battle of Ypres.

By August 28th 1917 they were in the dug outs at the Yser Canal, near Ypres. The country was different, but the conditions probably worse and the warfare familiar: ‘6 killed & 10 wounded (other ranks) . . . . . Situation quiet. Two other ranks killed & 7 wounded . . . . . . 1 killed, 4 wounded.’ Enemy aircraft bombing the transport lines was something new, and the attack was recorded as ‘killing 13 horses & wounding 7 horses.’ When considering the carnage amongst the men we forget how the animals suffered. Despite the new mechanised transport available, the horse was still the mainstay of the supply route, especially in the mud, and in the Great War some 8,000,000 horses were killed.

On September 20th the 2/7th Battalion, London Regiment managed a small advance and under intense artillery fire the 2/11th moved to take up their original position. The Germans counter attacked and although beaten off 10 men were killed and 38 wounded. Later that month while out of the line they received a draft to replace their depleted ranks; 5 officers and 279 other ranks for a Battalion whose full strength would normally be about a 1,000 men.

In January 1918 orders were received for the Battalion to be disbanded. Some officers and men were transferred to the 1/20th Battalion, London Regiment and others to the 1/21st. On the 30th the remainder, 8 officers and 240 other ranks, left for the 1/22nd Battalion, London Regiment and it is almost certain that this was when George moved to his new Regiment in France. They were also battle hardened and had also suffered terrible losses. On January 22nd their recorded trench strength was down to 20 officers and 359 other ranks. Another 149 men were on ration strength - men who had to be fed, but not available to fight. That brought the total to 529 - it should have been around 1,000. They clearly needed reinforcements so when George and the other men arrived on February 3rd they would have been welcome and although numbers had dropped in transit they added another 189 men to the Battalion’s strength. When they arrived the 1/22nd had just got to Bertincourt, they were quickly absorbed and the Battalion moved on to Trescault and back into the trenches. Soon afterwards about 70 men were working in the front line, and although there was no obvious cause, one man felt his throat swelling and reported that he thought that he had been gassed. Within a few hours seventy percent of the Company were casualties ‘some being so bad that they acted as though they had temporarily lost their reason.’

Little things meant a lot to the men and they must have gained much pleasure from the gifts which arrived from Queen Alexandra’s Field Force Fund. The parcels contained towels or handkerchiefs, soap or candles, stationery, chocolate or sweets and cigarettes. There were also mittens and footballs. The Germans rather spoiled the fun because they sent over about 200 shells. The horrors of war continued as ‘normal’, broken by rest spells, when they sometimes managed to enjoy baths and an opportunity to try to remove the grime and lice that lived on the men. They also enjoyed cinema evenings and occasionally the Battalion troupe of Follies known as the Bermondsey Butterflies would perform - each an opportunity of a few hours of distraction from the war, a chance to forget.

The massive German Spring Offensive, code named Operation Michael or Kaiserschlacht, commenced on March 21st and has been mentioned in previous chapters. George and his Battalion were in camp, but were immediately ordered forward, passing through a heavy gas shell barrage on the way. They did not come under direct attack until the 24th when they were forced back, regrouped, forced back, regrouped and then forced back yet again. Sometimes this was through pressure from the enemy and sometimes because German success on the left or right put them at risk of being outflanked and cut off. The situation along the front was chaotic, but the retirement of the 1/22nd was orderly. On March 24th they were back to High Wood, a location that had cost them dearly to capture in September 1916 and they were still retreating. By April they had retired to the area around Martinsart, but the fighting was still fierce: ‘This line was (to be) consolidated & prepared to hold at all costs.’ On the 7th they were relieved.

The situation, which was desperate for the Allied forces, eased as the German losses increased and their supply lines became over-extended. The initial high level of success could not be maintained, but it had cost all sides dearly, the allies total was over 250,000 men and the Germans nearly 240,000, including many of their specialist ‘shock troops’. Operation Michael is officially recorded as ending on the 5th. At the end of April the 1/22nd found time to record their casualties for March and April; 2 officers and 24 other ranks killed in action, 6 officers and 156 other ranks wounded. These numbers included 6 who were gassed and 2 who were wounded, but remained at their post. 1 officer and 30 other ranks were missing – a total of 219 men. George was lucky, he was not one of them.

Over the next couple of months, trench warfare returned, albeit with the British lines some distance back from where they had been. In June a large trench night raid was planned for the 17th with 3 officers and 60 other ranks participating. George is recorded as killed in action on the 17th. There were certainly casualties on the raid and while it remains uncertain (he could have been killed before the raid, for example), it does seem likely that he died on that raid.

The British casualties for the raid were 1 officer wounded, 13 other ranks wounded and 5 men were recorded as missing. The official report suggests that the missing fell and died in No Man’s Land. The bodies of these men were probably not recovered and, as George’s body was never found, it seems likely that he was one of them.

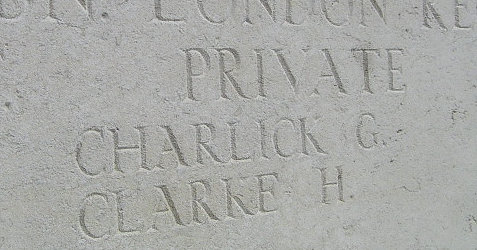

Whatever the facts, George’s name is recorded with others from his Battalion, on the panels at Pozieres Memorial. They record some 14,300 names of the missing from United Kingdom and South African Forces who died on the Somme between March 21st and August 7th 1918. The memorial is in countryside, a little distance from the village of Pozieres, and alongside the main road from Albert to Pozieres. The walls of the Memorial stand smartly to attention and face inwards protecting the names and the 2,755, mainly Australian, burials within.

Another memorial in Old Jamaica Road, Bermondsey, names the men of the 22nd Battalion, London Regiment (Queen’s), who died in the Great War and records over 800 names.

Additional Information

Text from the book: The Pride of Pirton.

*1 Believed more correctly, (County of London) Bn. London Regiment (The Queens's).

*2 Believed more correctly, (County of London) Bn. London Regiment (Finsbury Rifles).

Acknowledgments

The Pride of Pirton book – www.pirton.org.uk/prideofpirton Chris Ryan / Tony French / Jonty Wild