The following article is published with the kind permission of the author George Wilson, Hertfordshire Constabulary Great War Society and Dr. F.R.J. Newman PhD - editor of Trench Foot Notes.

THE DEFEAT OF THE GERMAN ARMY BY JAPANESE

AND BRITISH FORCES AT TSINGATO (CHINA) IN NOVEMBER 1914

George Wilson

As the end of the First World War commemorations draw to a close, most members of the public associate the Allied victory with four years of bloody conflict fought on a truly industrial scale, principally on the Western Front, resulting in horrendous casualties. To a lesser degree there is some rudimentary knowledge of other theatres of war, for example the Middle East and Gallipoli, but early in the war there were a number of smaller and largely unknown engagements between the Allies and Germany elsewhere, including South Africa and China. It was in the latter country the first allied victory was achieved in November 1914 at the Battle of Tsingtao, (sometimes called Tsingtau): modern name Quindao. A very welcome boost as they struggled to contain German advances on the Western Front.

Germany like other European countries (including Great Britain) sought to expand its influence in the Far East, by meddling in national and local government - China was a prime example. In 1898 Germany forced China to transfer Kiaochow in Shandong province to them on a ninety nine year lease. Then they began to assert their influence across the rest of the province by expanding the city and port of Tsingtao. It is located on the tip of the peninsula on a bay on the north-east coast of China; here they built a railway line, a commercial harbour and dry docks. It became a fortified naval base, the home of the German Navy’s Asiatic Squadron. Overall the German influence meant the province virtually became a German Protectorate.

The German Squadron commanded by Vice Admiral Graf von Spee, consisted of 2 armoured cruisers - Scharnhorst and Gneisenau together with the light cruisers – Emden, Nurnberg and Leipzig, a powerful force numerically comparable to, but technically superior to British naval forces based in Hong Kong.

Prior to the Great War, both Japan and Britain had become alarmed at the potential threat from Germany imperialistic intentions. Following the outbreak of war the threat to British interests in the Far East including troop convoys from Australia and New Zealand to Europe, prompted Britain to seek Japanese assistance in countering the real danger posed by German sea power. This was despite Britain being alarmed at the prospect of much increased Japanese power in the region. Japan judged Germany to be a long term threat to her security, manifested by the construction of the heavily fortified port of Tsingtao. As a result it willingly supported the prospect of military action to dislodge the German military from the area becoming the senior partner in the venture.

Meanwhile, China had declared her neutrality, but due to political and military weakness was unable to curtail the military activities of the three powerful nations meaning conflict was inevitable.

The Germans had been at Tsingtao for 12 years before hostilities began, giving them plenty of time to prepare adequate defences. The peninsula around the port is spanned by two ranges of low hills. On the nearest hills to Tsingtao they had constructed three ferro-concrete forts (named Moltke, Iltis and Bismark) protected by a number of 4 inch, 6 inch and 9.4 guns; in addition Bismarck the highest hill in the centre of the peninsula had four 11 inch howitzers. Hsian-Ni-Wa fort was built on a promontory to the south-east and housed revolving 9.4 inch and 6 inch guns. The valley of the Hai-Po river 4 miles north-east of the port was over a mile wide, with bare sloping sides making it a formidable obstacle and an excellent defence line. Concrete redoubts had been built with a 10 foot ditch running from sea to sea. A 6 foot wall had also been constructed with the immediate area strewn with land mines. It had one major fault – if this line fell the entire peninsula would be lost. The third defence line on the second range of hills north-east of Tsingtao and beyond the river was the 1,200 high Prinz Heinrich Hill on the eastern side of the peninsula was ten miles wide at this juncture and impossible to man with the garrison available. Although there were some trench fortifications there were none on the hill itself, a negligence that was to prove decisive; if this obstacle was overcome the entire southern end of the defence network would also be lost.

When hostilities began the defenders had 53 heavy guns and howitzers, 77 lighter guns and 47 machine guns in position. The number of defenders stationed there is uncertain. The Marine Artillery and 3rd Marine Battalion totalled 3,000, forming the backbone of the garrison, but these numbers were augmented by reservists and volunteers who flocked to the base from all over the Pacific region. With the crews of the smaller ships in the harbour, the total garrison was just under 6,000. The sole aircraft was a monoplane piloted by Oberleutenant-zur-See Pluschow.

Sufficient stores to last a year were stockpiled, the water supply was likely to be cut off, but there were wells and a distilling plant inside the city. A large shipment of ammunition on its way when war was declared never arrived – a grave setback for the defenders. Towards the end of July the civilian population was reduced from 55,000 to 30,000. In overall command was the naval governor of Tsingtao – Meyer Waldeck.

The German Asiatic Squadron left Tsingtao on 4th August 1914. History records that the Squadron fought and won a victory against obsolete British Navy ships in the battle of Coronel off Chile on 11th November. The British Navy exacted revenge on 8th December when it destroyed the German Asiatic Squadron in the waters around the Falkland Islands, during which Admiral Graf von Spree lost his life. The danger posed to British and Allied shipping from single German raiders was manifested by the German cruiser Emden. It was not part of the German Asiatic Squadron; instead it roamed the Indian Ocean causing panic, sinking 16 British merchant ships, a Russian light cruiser and a French destroyer, before it was sunk on 9th November by the Australian cruiser Sydney off the Cocos Islands.

The remaining German ships in Tsingtao were an old destroyer, 5 gunboats and the obsolete Austrian cruiser Kaiseria Elizabeth. These vessels could not challenge the Japanese naval task force – 4 battleships, 17 cruisers, 24 destroyers and supporting vessels, plus air support which was charged with enforcing a total sea blockade and supporting the invasion force. The British Navy were involved in the blockade using the battleship HMS Triumph and a destroyer HMS Usk. The German defenders realising the dangers of the sea power ranged against them had heavily mined 8 miles of sea around Tsingtao.

Japan issued an ultimatum to Germany on 15th August 1914 telling her to withdraw her warships from Chinese and Japanese waters and surrender the temporary leased territory of Kiaochow. It expired on 23rd August without a German reply. Anticipating the outcome, the Japanese were already making plans and formally declared war. For years they had closely observed Tsingtao and knew details of most of the fortifications etc. Lieutenant General Kamio commanded the invasion force of 50,000 men, 12,000 horses, 103 heavy guns or howitzers and 42 field or mountain guns.

The total Japanese sea blockade due to heavy storms could not be put in place until 27th August. Once in position the Japanese army landed at Laichow Bay, ignored Chinese neutrality by advancing into their territory on to Kioachau. Their progress was painfully slow, with both the advance and consolidation being hampered by the worst storms for 60 years. The weather did not help the German defenders either, many of their trench systems were filled with water, whilst many mines became useless; in essence much of their careful preparations were nullified.

On 27th September the attack began with tremendous artillery barrages with supporting naval gunfire. Despite German resistance by the 28th the Japanese had driven the defenders into their fortified positions in Tsingtao behind the line of hill forts. The next day the Germans attempted to drive the attackers back, but it was a total failure. They were now ensconced within their defensive perimeter, with no outside help possible.

The British too had an imperial presence in China - the British Army in their North China Command comprised 8 battalions (3 British and 5 Indian). Although no mobilisation orders had been received, the 2nd Battalion South Wales Borderers had been holding itself in readiness at its base in Tientsin, awaiting orders. When war was declared it was told to be ready to move at short notice; the order was issued on 17th September and two days later the battalion embarked in three small transports escorted by HMS Triumph and Usk (withdrawn from assisting the Japanese naval blockade). The embarkation return showed 22 officers and 910 other ranks commanded by Brigadier General Nathaniel Walter Barnardiston, a Boer War veteran and a former lieutenant colonel in the Middlesex Regiment.

On 22nd September the convoy reached Laoshan Bay located on the east coast of Shantung Peninsula, about 40 miles north east of Tsingtao, was crowded with Japanese shipping. Disembarkation began at 0800 hours the next day, men got ashore quite easily, but unloading 300 mules, carts, ammunition plus 14 days supplies was a major problem. By the 24th the work had been completed, but it took a further 24 hours to reach a base supply depot just 6 miles away.

As already stated before the arrival of the British contingent the weather had been atrocious; the road or rather track used by the British to reach the conflict area was in bad condition, narrow and heavily congested by the movements of the large Japanese army and their equipment using the same road. British problems were compounded when the Japanese commander proposed to use them in the centre of the line and not on the left where it could have been in touch with the British ships. This entailed a longer march and greatly increased supply difficulties from day one of the advance, including the battalion being placed on half rations due to lack of transport. For the same reason crowbars, axes and most picks and shovels (necessary to engage in trench warfare) had to be left behind. On the second day the South Wales Borderers reached Tsimo after a 14 mile slog, followed by another 9 mile to reach to Liuting, where it could hear the sound of battle and see the masts of German vessels in Kiaochao Bay.

The next day (27th September) it was the intention that the advanced German position north east of Tsingtao would be attacked at dawn with the South Wales Borderers assigned a front of 1,600 yards to seize a redoubt. However the German defenders had decamped during the night so the battalion was not engaged; they were merely required to march another 10 miles bringing them to a position 3 miles from the next defensive positions.

The British were still lacking in equipment and spent the next ten days in situ, whilst the Japanese brought forward heavy artillery, ammunition and siege equipment before the initial stages of the investment began. The weather was still very poor, so called roads had been turned into rivers of mud severely hampering operations. To make matters worse the soldiers were dressed in thin summer clothing with one blanket and waterproof, making them particularly ill equipped to cope with the elements.

On 10th October the British commander was given orders from General Kamio for the South Wales Borderers to take its place in the front line on a 600 yards frontage. Prior to this it had sustained a few casualties from shell fire, but considering the weather and living conditions the sick rate was extremely low. This said much about their fortitude, despite inadequate food being available, much digging was required, no wheeled transport was available, requiring rations, ammunitions and stores including heavy beams for trench systems had to be carried to the front line by hand over a mile and a half of tracks often knee deep in mud, increasingly under shell fire as they neared the German main defences.

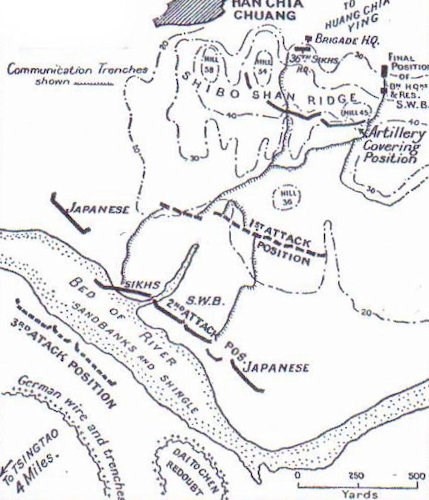

The British infantry was now established on Shibosan Ridge, where the German defences were particularly strong with a line of redoubts supported by field and machine guns, with trenches linking the redoubts, surrounded by a mass of wire entanglements. To overcome the defences it was necessary to proceed by regular siege operations by digging a succession of trench lines at intervals known as the Artillery Covering Position, together with the First Second and Third Attack Positions, connected by communication trenches. The southern slope of the Ridge was in full view of the Germans, therefore work was only possible at night. By day picquets held the most advanced positions, whilst the rest of the companies toiled carrying out mundane, but necessary trench supporting roles. Some relief came when a Japanese engineering company was allocated to assist.

On 28th October a half battalion of the 36th Sikh Regiment which had landed a week earlier reached the front line with one of its companies taking over responsibility on the right of the South Wales Borderers frontage. Two days later the British contingent took over the Artillery Covering Position just over the crest of the Ridge; the artillery took up position and unleashed a tremendous barrage on the following day. It was extremely effective – the forts and redoubts were severely damaged and oil tanks near the dockyard set on fire.

On 1st November work began on the First Attack Position, followed shortly by arrangements being made for the occupation of the Second Attack Position, a further 400 yards down the slope. Until this juncture the British attackers had been fortunate in suffering light casualties. But as they advanced to the three attack positions they were subjected to heavy German shelling, aided by searchlights, inevitably increasing casualties, especially during the night of 5th/6th November. At this time Brigadier General Barnardiston told Major General Kamio he did not consider the Third Attack Position fit for permanent occupation. He was informed that in the general scheme of operations it was required to be held: Barnardiston complied by the use of picquets.

As night fell the British became aware of unusual activity around their position with searchlights playing freely with heavy firing going on all night. In fact the Japanese were attacking the defenders and took a fort at the western end of the line. As a result just as their main assault was about to be delivered at 0700 hours on 7th November, a white flag was raised: The siege was over.

The sudden termination of the fight meant the British had no chance of distinguishing itself in the final stage of the operation during the night of 6th/7th November. The Japanese intention to force the issue, whether deliberate or the result of a sudden decision was never communicated to Barnardiston or the South Wales Borderers. Not having taken part in the final assault, the British and Sikhs during the battle for Tsingtao sustained fairly light casualties – 14 men killed or died of wounds, plus 2 officers and 34 other ranks from the SWB wounded.

The success of the Japanese (with limited support from the British) was due to various factors. At various stages of the operation it deployed 60,000 men plus copious supplies of guns and ancillary siege material, with total command of the sea by a naval blockade. Major General Kamio despite the atrocious weather was very patient in his build-up. Not for him massed frontal attacks, instead he employed unstoppable artillery barrages, which plus naval gunfire gradually degraded the defenders defences resulting in almost total destruction of forts and redoubts. He also used the procedure of building saps to approach the German defences before launching his attacks. The Japanese total casualties were 1,455 killed and 4,200 wounded – many caused by stiff German resistance during the final assault.

As already mentioned the German defenders were greatly outnumbered, once the Asiatic Squadron had left Tsingtao they were in an impossible position, from 27th August they were totally cut off from the outside world. No doubt the atrocious weather slowed down the attack, but the defenders made the best use of their precarious situation, and it is a tribute to them it took the attackers six weeks to force a capitulation. German casualties were put at 200 killed and 4,043 taken prisoner, (some sources suggest their total casualties were nearer 1,000). 201 officers including the Governor and 3,481 other ranks were taken to Japan as POWs. The loss of Tsingtao was a bitter blow for Germany, especially within a few weeks Japanese, Australian and New Zealand forces seized the remaining German territories in the Pacific, allowing Allied naval forces to remove German merchant shipping and port facilities from the area.

Major General Kamio was appointed Governor of Tsingtao, which remained in Japanese hands until 1922 when it reverted to Chinese control. As a result of their efforts the 2nd Battalion South Wales Borderers were awarded the battle honour – Tsingtao. The three Despatches of Brigadier General Barnardiston relating to British involvement in the battle were published in a Supplement to the London Gazette on Tuesday 30th May 1916. In the final sentence of the third report, he paid tribute to the British and Indian efforts. “The troops under my command have behaved extremely well under trying conditions of weather and those inseparable from siege warfare, and all ranks have worked loyally and hard”

Within 10 days at the end of the battle the South Wales Borderers left Tsingtao, where during the march to their embarkation point the route was lined by Japanese troops; they also received fulsome praise on their departure for England via Hong Kong from the Mikado and senior Japanese officials. On 10th January 1915 they arrived in Plymouth where it joined the 87th Brigade of the 29th Division. The Battalion subsequently saw service in Gallipoli, the Western Front and as part of the Army of Occupation in the Rhineland. Brigadier General Barnardiston after his return from China was promoted to major general; he commanded the 39th Division during 1915-1916, before being made Chief of the British Military Mission to Portugal (1916-1919).

Despite the comparatively light casualties sustained at Tsingtao, especially when judged against the their very heavy casualties at Gallipoli and the Western Front, the 2nd Battalion of the South Wales Borderers did not have an easy time at Tsingtao. Their difficulties (amongst others) are succinctly described “….want of tools and maps, shortage of rations, the absence of adequate shelter and fuel, summer clothing which was ill-suited to the severe weather; perhaps the most serious was the difficulty of co-operating with allies whose ways and whose language was unfamiliar”

Map of the Attack on Tsingtao

Major General Kamio & Brigadier General Barnardiston: September 1914

Sources:

National Archives

Imperial War Museum

National Army Museum

Regimental Museum South Wales Borderers/Royal Regiment of Wales

London Gazette

Commonwealth War Graves Commission

(Atkinson): The Medici Society

The Long Long Trail

Wikipedia