The following article is published with the kind permission of the author George Wilson, Hertfordshire Constabulary Great War Society and Dr. F.R.J. Newman PhD - editor of Trench Foot Notes.

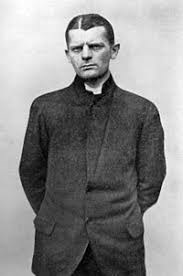

CARL HANS LODY

TRIED AND EXECUTED FOR SPYING FOR GERMANY

By George Wilson

In pre-First World War Britain, the growing threat of Germany created a climate in which popular novels about espionage thrived, for example Erskine Childers author of The Riddle of the Sands (1903) depicted a sophisticated German intelligence network laying the foundations for an invasion of Britain. In reality the truth was more prosaic. The National Archives summaries the situation “A small number of spies employed by the German Navy were active in pre-war Britain. But between August 1911 and July 1914, the War Office’s counter-espionage department arrested just 10 suspects. Britain’s own attempts to establish a spy network in Germany met with similarly little success” [1]

Despite the scepticism of many individuals of Germany’s ability to spy on Britain and her allies, the Imperial Defence Committee had already taken steps to counter the activities of enemy agents, articulated by the directors of naval and military intelligence. The result of these concerns was the appointment in 1909 of Vernon George Waldergrave Kell and Mansfield Smith-Cumming to head the newly created Secret Service Bureau.

Kell a regular army officer with the South Staffordshire Regiment, had seen service in Russia and China during the Boxer Rebellion; subsequently he served in the War Office as an intelligence analyst, a task made easier by fluency in German, Italian, French and Polish languages. Captain Mansfield Smith-Cumming was a naval officer employed in counter intelligence. As the threat of war with Germany increased, there was a pressing need to gather information about Germany’s expanding navy. This resulted in the division of the Secret Service Bureau – “Kell’s Home Section or the Security Service (later known as M.O.5g then M.I.5) would concentrate on the espionage threat within the United Kingdom. Whilst Cumming’s Foreign Section or the Secret Intelligence Service (later known as M.I.6) was tasked with gathering overseas intelligence on the nation’s potential enemies”[2]

Initially these two organisations had very few staff made up of officers and civilian support; between August 1914 and November 1918, the numbers increased from 19 to 844. Throughout the war, Kell worked very closely with Basil Thomson, head of the Special Branch and together with Mansfield-Cumming the two units were ‘on top of the German spying threat’. It was against this background that eleven spies of different nationalities including German, Swedish, Uruguayan and Brazilian were arrested and executed at the Tower of London for spying – Carl Hans Lody being the first one.

Lody was 39 years old at the outbreak of the First World War, a German national who, after completing a year’s service in the German Navy from 1900-1901, joined the Seewehr the Second Corps of the German Naval Reserve, before entering the merchant service. As a result he had travelled a great deal, taking employment on English, Norwegian and American ships. In 1912 he married an American woman of German descent; the marriage was short lived and by the Spring of 1914 he had been employed as a tourist agent and travelled around the world four times in the company of 550 – 600 English, British and American citizens, and was in Berlin during the critical days of July 1914.

Following a serious illness, Lody felt he could no longer continue his seafaring career consequently he applied to be released from any naval service. He was interviewed on a number of occasions by a senior German naval officer who suggested he visit England on his way to New York and to “give notice of my safe arrival in England and remain until the first naval encounter had taken place between the two great powers and gather information as regards the actual losses of the British fleet, and then I was at liberty to proceed to New York”[3] (Lody later stated he was unhappy with this suggestion, but he was under no illusion that in the military world it was plain there was a requirement for him to comply). In fact German naval records show Lody was a willing volunteer.

Between 6th and 19th August, he received by post a plain white envelope containing an American passport already signed by a Charles A. Inglis, a genuine person who had been told by the Germans that his passport had been lost after he had applied to the American Embassy for a visa to enable him to continue his travels in Europe, which had been passed to the German Foreign Office for attention.

On 14th August pretending to be an American tourist by using Inglis’s passport, Lody left Hamburg for neutral Norway, from where he took a ship to Newcastle arriving on 27th August. He then travelled to Edinburgh booking into North British Station Hotel (Room 318). On 30th August he went to the telegraph office at the city’s main post office. Here a William Mills a counter clerk noticed several procedural mistakes on the telegram written by Lody including it only bore the signature of “Charles”. It was addressed to “Adolph Burchard at 4 Trottninggatan, Stockholm”. So far as Lody was concerned the message now bearing the full signature of Inglis would be despatched. The telegram said: “Must cancel Johnson very ill last four days shall leave shortly”[4]

However, unknown to him the British intelligence service were intercepting and reading any mail and telegrams regarded as suspicious. In this case the address of Burchard was known to them as a front for German intelligence. On 1st September Lody moved to Bedford House, 12 Drumsheugh Gardens, Edinburgh, again registering in the name of Charles A. Inglis.

Why was Edinburgh regarded by the German authorities of particular interest? The Firth of Forth, the large estuary to the north of Edinburgh was of great strategic importance. As well as being the main seaward approach to the Scottish capital, it was used as an anchorage by dozens of Royal Navy ships, heavily defended by gun batteries and minefields to protect it against attacks from the sea. It was also thought to be an ideal location, where following any major sea battles, British losses might be ascertained.

Lody had very little training for espionage. His only means of communications with his German superiors was by telegrams and letters to neutral countries. He sent a number of telegrams using a simple code, but other incriminating messages were sent in plain text without any coding. As already mentioned he had no idea MI.5 were monitoring letters and telegrams and his messages would be intercepted.

Lody’s activities were detected in his very first messages sent to Adolph Burchard in Stockholm, but his true identity was not known at this stage as he signed his messages “Charles” or “Nazi” (the latter alias had no connection with Adolph Hitler’s party. “Nazi” was a short form of the name “Ignatz” and also a nickname for Austro-Hungarian soldiers).

During his time in Edinburgh, Lody sent messages which the British authorities allowed to go through because they contained misleading information that would alarm the German, but cause no harm to the British. For example Lody sent a message reporting an infamous, but untrue rumour that thousands of Russian troops had been sent to fight on the Western Front.

Lody travelled to Dublin in Southern Ireland on 29th September, via Liverpool. He took the opportunity to write a detailed letter in German describing ships in the harbour and conversations that he had overheard. Unlike some of his earlier reports, it contained information of real military value to the Germans, but again was written without any coding.

Part of the letter referred to a Cunard liner – The Aquitania: “All the plates from the top deck downward that is starting at the top deck have been re-riveted and 6 plates including the bow have not been repaired yet… I started a conversation with the dock watchman who told me that the Aquitania was to be armed with 12 guns of large calibre and several small ones. The ship is painted greyish black”[5]

Postal censors intercepted the letter and having read the contents MI.5 decided to order his arrest. The police in Edinburgh were asked to assist and on 2nd October detective James Cameron was tasked with visiting hotels in the City to trace Charles A. Inglis. The officer discovered where Lody had been staying, and had stated his intention of going to Ireland for a few days. The information was relayed to MI.5 who requested the Royal Ulster Constabulary make enquiries to trace a suspected German spy posing as an American citizen Charles Inglis. By 7.23pm the same day the RUC stated Inglis had arrived in Dublin on 29th September and was believed to have gone to Killarney. At 9.45pm District Inspector Cheesman went to the Great Southern Hotel where he found Charles Inglis had arrived by the 3.18pm train.

Cheesman found Lody was not in his room, but he arrived shortly afterwards. Lody was asked if he was Charles Inglis. He replied “yes”, he was then arrested as a suspected German agent under the provisions of the Defence of the Realm Act. Lody was taken to the police barracks, where he was found to be in possession of the Inglis passport, £14 in German gold, 705 kroner in Norwegian bank notes and a small notebook. The notebook contained a list of cruisers that had been sunk in the North Sea, names and addresses of persons in Hamburg and Berlin and what appeared to be a cipher or key. In his bag was found a jacket and upon examination a tailor’s ticket was found sewn inside the breast pocket. This read: “J. Steinberg, Berlin, R.C.H. Lody 8.5.14”.

Lody was transferred to London and detained in Wellington Barracks in the custody of 3rd Battalion Grenadier Guards. By 7th October it had been decided that he should tried before a general court martial as soon as possible. The case was discussed by the Cabinet, and as a result by 21st October it was decided that Lody should be tried by the High Court and not by court martial for a war crime. Arrangements were also made to hand him over to the civil police. However this alteration was short-lived as Lody made a statement that he was a German citizen; on 22nd October the Cabinet decided to revert to the original plan.

His court martial took place on Friday 30th October, Saturday 31st October and Monday 2nd November 1914 at the Middlesex Guildhall. During the trials of later spies who were executed in the Tower of London, in the war, Lody’s trial was the only one not held in camera. The evidence was overwhelming. Evidence found on him at the time of his arrest and in his recovered property that he had left at the Roxburgh Hotel was conclusive.

During the proceedings Lody appeared affable, including the period he was cross examined by prosecuting counsel, apart from when he was asked who had sent him to England to spy. Newspaper reports said at this juncture he struggled to retain mastery of himself as to whether he should disclose the name. Emotionally he said: “I have pledged my honour not to name that name, I cannot do it”[6] During his trial the proceedings were widely reported in the press; his admission he was a German naval officer, plus his display of honour and patriotism attracted widespread admiration both in Britain and Germany.

On 2nd November the court martial assembled for the third time to hear the speeches of the counsel. A Mr Elliott defence counsel intimated he did not propose to call evidence on behalf of the accused. For the Crown, Mr Bodkin succinctly stated why Lody had been charged with a capital offence: “Lody was a skilled and dangerous man; the class of man against which international military law was aimed; and it was such a tribunal as this to protect the interests of the state”[7]

At the conclusion of the speeches, and after a few formalities, the members of the court martial withdrew to consider their findings. After an absence of 6 minutes they returned to their seats; their findings, though not disclosed, were obvious. For instead of ordering the prisoner’s release, the president asked if Lody wished to make any statement. Lody declined, and was asked twice more if he wished to say anything; again he declined. The court was then cleared for sentence. On the clearest evidence there was only one possible outcome: a guilty verdict with the inevitable death sentence being imposed.

On 4th November written instructions were issued to the general officer commanding London District, confirming that His Majesty had confirmed the findings of the court and that promulgation of the sentence should take place the following morning. There must then be at least 18 hours between Lody being told of his fate and his shooting. On 5th November a letter was sent to Major General Pipon, the Major of the Tower of London by the London District commander, directing him to quickly make the necessary secret arrangements: The Tower of London was the only possible place of execution. On the night of 5th- 6th November, Lody was taken by police van to the Tower of London, where he was informed of his forthcoming execution.

Carl Hans Lody

As a result, Lody wrote 2 letters, one to relations in Stuggart. Part of the letter said: “A hero’s death on the battlefield is certainly finer, but such is not to be my lot, and I die here in the Enemy’s country silent and unknown, but the consciousness that I die in the service of the Fatherland makes death easy”[8] The second letter addressed to the Commanding Officer of the 3rd Battalion Grenadier Guards, Wellington Barracks said: “I feel it is my duty as a German officer to express my sincere thanks and appreciation towards the staff of officers and men who were in charge of my person during my confinement.

Their kind and considered treatment has called my highest esteem and admiration as regards good fellowship even towards the enemy and if I may be permitted, I would thank you for making this known to them.

I am, Sir with profound respect: Carl Hans Lody. Senior Lieutenant, Imperial German Res. II.[9]

Early the following morning 6th November, on a cold foggy and bleak morning Lody was taken from his cell (29 the Casemates) and accompanied by the escort together with the chaplain and the Assistant Provost Marshal. Lody is alleged to have said to the military police officer: “I suppose that you will not care to shake hands with a German spy?” “No. But I will shake hands with a brave man” A few minutes later the procession including the 8 man firing squad from the 3rd Battalion Grenadier Guards disappeared through the doorway of the miniature rifle range (here spies were blindfolded and secured by straps to a chair), A few minutes later the muffled sounds of a single volley was heard.

Carls Hans Lody paid the ultimate price for spying; the first person to be executed in the Tower of London since 1780 –134 years previously.

Lody was buried in an unmarked grave in the East London Cemetery in Plaistow, which also received the bodies of other spies executed in the war. In 1924 the grave received a marker. The headstone was destroyed by a Luftwaffe bomb in the Second World War, and the present headstone was erected in 1974.

Sources:

Book: Shot In The Tower

Websites: National Archives, MI5 Security Service, Spartacus Educational Government UK, Western Front Association (article by David Tattersfield), Wikipedia

[1] National Archives.Gov.Uk/pathways.firstworldwar

[2] Leonard Sellers: Shot In The Tower (Barnsley: Pen & Sword Military, 2009), p. 3

[3] Leonard Sellers: Shot In The Tower, p. 18

[4] Leonard Sellers: Shot In The Tower, p. 20

[5] Leonard Sellers: Shot In The Tower, p. 28

[6] Leonard Sellers: Shot In The Tower, p. 37

[7] Leonard Sellers: Shot In The Tower, p.38

[8] Leonard Sellers: Shot In The Tower, p. 41

[9] Leonard Sellers: Shot In the Tower, p. 41